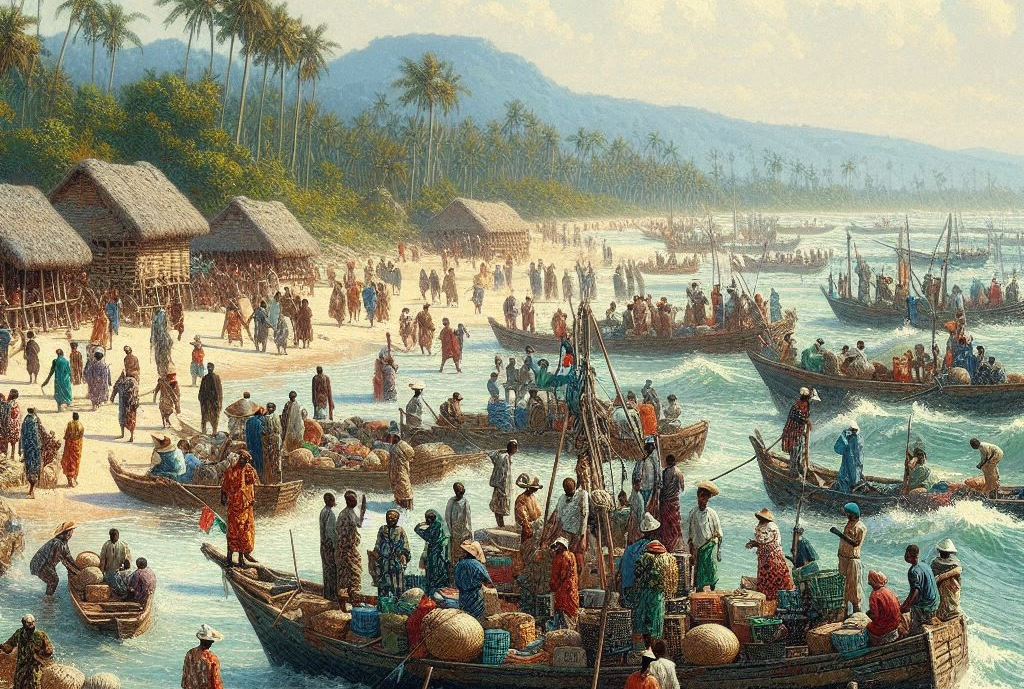

The global impact of climate change is escalating. Africa, as a significant part of the Global South, is increasingly turning to its rich heritage of Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) for sustainable solutions. Aqua-Farms Organization has recognized the immense value of TEK in developing resilient and sustainable practices for our marine conservation and community livelihood improvement projects across the coast of East Africa. Many National Adaptation Plans (NAPs) recognize the need to integrate Indigenous Local Knowledge (ILK) and explicitly list this in the official documents. However, it is unclear how this is translated into concrete projects and initiatives on the ground.

Understanding African Traditional Ecological Knowledge

Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) in Africa refers to the evolving body of knowledge, practices, and beliefs about the relationships between living beings and our environment, passed down through generations in our indigenous and local communities. It is an holistic approach to understanding nature offering unique insights that can complement and enhance Western scientific methods in addressing climate solutions.

“There is growing recognition that Indigenous perspectives should be front and center in climate change responses.”

The sentiment resonates strongly across Africa, where TEK has been a cornerstone of survival and adaptation for centuries.

The Relevance of African TEK in Climate Change Mitigation

The significance of African TEK in climate change strategies stems from its:

- Holistic Approach: African TEK views humans as an integral part of the ecosystem, this creates a balanced relationship with nature.

- Long-term Observations: Generations of careful environmental observations provide valuable data on climate patterns and changes specific to African ecosystems.

- Adaptive Strategies: African communities have developed flexible and resilient practices to cope with environmental variability unique to the continent.

- Sustainable Resource Management: African TEK often incorporates sustainable harvesting and conservation practices tailored to local ecosystems.

Challenges and Opportunities

While the value of African TEK is increasingly recognized, several challenges remain:

– Knowledge Loss: Rapid modernization and displacement of indigenous communities threaten the preservation of TEK.

– Integration with Modern Science: There’s a need for better frameworks to integrate TEK with contemporary scientific approaches.

– Recognition and Rights: Ensuring that African indigenous communities’ rights and knowledge are respected and protected is crucial.

However, these challenges also present opportunities for collaboration and innovation.

“It’s important for tribal people to be at the table. We have a lot of knowledge; we have a lot of experience on how to protect and restore natural resources.”

Three shifts that could help to transform climate research approaches to be more inclusive:

-

- A change of the programmatic mindset that guides most scientific work is required. The change would allow scientists to reconsider what “science” means and what can be labeled as scientific outcomes. Climate research is exclusionary, framed by Western science-based approaches, and though traditional knowledge does follow the same path, this knowledge system is grounded on careful observation of environmental changes that indigenous communities have relied on for many decades to cope with climate challenges.

- Limited funding flows to climate research in general, and more specifically to local knowledge evidence in the global south, is a major barrier (Climate Financing agenda). A recent study on thematic prioritization of funding for climate change research in Africa shows that while institutions from the global north—principally Europe and North America—received 78% of funding for climate research, African institutions received only 14.5%. Most local and indigenous knowledge is generated in the global south—Africa, Latin America, and Asia—and this funding discrepancy means that climate-related local knowledge is not fully captured in climate research to create space for the integration. This suggests that funding bodies need to set more dedicated allocations for documenting the practical integration of local knowledge.

- The integration of local knowledge/indigenous knowledge and scientific knowledge should not just be seen as a combination of the two knowledge systems. The integration should be part of a more complex co-production process where climate scholars and local/indigenous communities interact effectively and are interested in questioning how local knowledge resonates in the scientific framing or vice-versa. This cooperation calls for an ethical shift, humility from both “scientists” and local communities for mutual learning with no “asymmetry of power” that gives one group more power to determine the direction that the co-operation takes.

- A change of the programmatic mindset that guides most scientific work is required. The change would allow scientists to reconsider what “science” means and what can be labeled as scientific outcomes. Climate research is exclusionary, framed by Western science-based approaches, and though traditional knowledge does follow the same path, this knowledge system is grounded on careful observation of environmental changes that indigenous communities have relied on for many decades to cope with climate challenges.

Conclusion

As we at Aqua-Farms Organization continue to develop sustainable practices in Africa, we recognize the immense value of Traditional Ecological Knowledge. The wisdom of indigenous and local communities in Tanzania and Africa at large offers a treasure package of sustainable solutions to our climate challenges. Integrating this knowledge with modern scientific approaches, we can create grounds for a more resilient and sustainable future for the continent and beyond.

In the words of an African perspective on climate change, “Everything we are as Indigenous people is connected to the place.”

This profound connection to the environment, embodied in African TEK, may well be the key to addressing our global climate crisis. It’s time we listen, learn, and act on this ancient wisdom for the benefit of our planet and future generations.

Sources

Javis Bashabula

Communications & Knowledge Management Lead - AFO